In-Engine Narrative Compiler - Part 2: Data Is King

A quick recap

This is a continuation of Part one of this series. In this post I’ll be talking about data storage, assets, and why writing less code that can process more data is a good thing.

Implementation Details That Matter

So, onto the actual implementation of this lovely language. My first question was, “how do we get this into a format that Unity can actually understand?” - fortunately, given my love for driving games with data and not code as much as humanly possible, I was already aware that Unity supports a feature called ScriptableObjects. You can find more information about how those work here, but for the sake of this post I shall summarise. A ScriptableObject is Unity’s mechanism for supporting data containers as assets - you can create them, modify their values in the inspector, and have MonoBehaviours consume them and react to the data they contain. Since implementations of ScriptableObjects are also C# classes that inherit the base class, you can also add actual functionality to a ScriptableObject. However, this is rather rare due to the nature of ScriptableObjects being primarily just data containers.

Did I get the general idea across? Awesome! Let’s look at the ScriptableObject I implemented to support narrative scripting then!

namespace ACHNarrativeDriver.ScriptableObjects

{

[CreateAssetMenu(fileName = "NewNarrativeSequence", menuName = "ACH Narrative Driver / NarrativeSequence")]

public class NarrativeSequence : ScriptableObject

{

[Serializable]

public class CharacterDialogueInfo

{

[SerializeField] private Character _character;

[SerializeField] private bool _hasPoseIndex;

[SerializeField] private int _poseIndex;

[SerializeField] private bool _hasPlayMusicIndex;

[SerializeField] private int _playMusicIndex;

[SerializeField] private bool _hasPlaySoundEffectIndex;

[SerializeField] private int _playSoundEffectIndex;

[SerializeField] private string _text;

public Character Character

{

get => _character;

set => _character = value;

}

public int? PoseIndex

{

get => _hasPoseIndex ? _poseIndex : null;

set

{

if (value.HasValue)

{

_poseIndex = value.Value;

_hasPoseIndex = true;

}

else

{

_hasPoseIndex = false;

}

}

}

public int? PlayMusicIndex

{

get => _hasPlayMusicIndex ? _playMusicIndex : null;

set

{

if (value.HasValue)

{

_playMusicIndex = value.Value;

_hasPlayMusicIndex = true;

}

else

{

_hasPlayMusicIndex = false;

}

}

}

public int? PlaySoundEffectIndex

{

get => _hasPlaySoundEffectIndex ? _playSoundEffectIndex : null;

set

{

if (value.HasValue)

{

_playSoundEffectIndex = value.Value;

_hasPlaySoundEffectIndex = true;

}

else

{

_hasPlaySoundEffectIndex = false;

}

}

}

public string Text

{

get => _text;

set => _text = value;

}

public override string ToString()

{

return $"Character: {Character.Name}, HasPoseIndex: {_hasPoseIndex}, {(_hasPoseIndex ? "PoseIndex: " + PoseIndex + ", " : string.Empty)}Text: {Text}";

}

}

[Serializable]

public class ChoiceInfo

{

[SerializeField] private string _choiceText;

[SerializeField] private NarrativeSequence _narrativeResponse;

public string ChoiceText

{

get => _choiceText;

set => _choiceText = value;

}

public NarrativeSequence NarrativeResponse

{

get => _narrativeResponse;

set => _narrativeResponse = value;

}

}

[SerializeField] private Sprite _backgroundSprite;

[SerializeField] private NarrativeSequence _nextSequence;

[SerializeField] private List<AudioClip> _musicFiles;

[SerializeField] private List<AudioClip> _soundEffectFiles;

[SerializeField] private List<CharacterDialogueInfo> _characterDialoguePairs;

[SerializeField] private List<ChoiceInfo> _choices;

public List<ChoiceInfo> Choices

{

get => _choices;

set => _choices = value;

}

public NarrativeSequence NextSequence

{

get => _nextSequence;

set => _nextSequence = value;

}

public List<AudioClip> MusicFiles

{

get => _musicFiles;

set => _musicFiles = value;

}

public List<AudioClip> SoundEffectFiles

{

get => _soundEffectFiles;

set => _soundEffectFiles = value;

}

public List<CharacterDialogueInfo> CharacterDialoguePairs

{

get => _characterDialoguePairs;

set => _characterDialoguePairs = value;

}

public Sprite BackgroundSprite

{

get => _backgroundSprite;

set => _backgroundSprite = value;

}

[field: SerializeField, HideInInspector]

public string SourceScript { get; set; }

}

}

Woah. Okay. That’s a lot of properties and other very cool modern C# stuff. Some of it possibly a hangover from the late night game jam debugging sessions where I was losing my mind, as all game developers do! So, lets break it down a bit.

[SerializeField] private Sprite _backgroundSprite;

[SerializeField] private NarrativeSequence _nextSequence;

[SerializeField] private List<AudioClip> _musicFiles;

[SerializeField] private List<AudioClip> _soundEffectFiles;

[SerializeField] private List<CharacterDialogueInfo> _characterDialoguePairs;

[SerializeField] private List<ChoiceInfo> _choices;

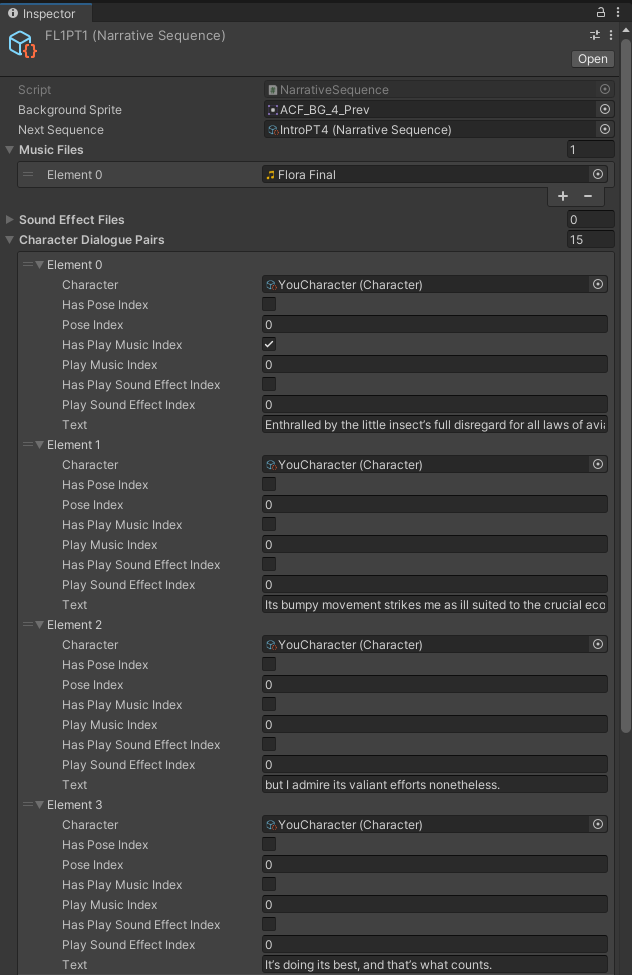

These are all the things that eventually made it into the narrative tool due to the requirements of the game jam; the current environment background, the next narrative sequence to execute, the dialogue and character information for the current sequence, and any music and sound effect files that the narrative file might rely on too! I also organised some of the data into nested serialised types, such as CharacterDialogueInfo, to help streamline and group data in a more organised fashion. You don’t need these nested types, but it certainly made the inspector look nicer!

The reason we exposed these members to the inspector using SerializeField was so that if the UI tool I bolted on top of this thing broke, we could edit the scriptables directly. Thankfully, this didn’t happen. Happy face.

I also persisted the original source code into the asset itself using this:

[field: SerializeField, HideInInspector]

public string SourceScript { get; set; }

To not drag out the explanation of this piece of code too much, it is hidden from the inspector because the auto-generated field name is not only ugly, but also people shouldn’t be directly modifying this. This is so Unity can track changes easier with asset dirtying, amongst other things. Like the other members, this property is directly set by the compiler-ish tool.

The rest of the code is mostly just property accessors so that intellisense didn’t get totally clogged up with things I didn’t need to care about. It might be a game jam but I like keeping my autocomplete as relevant as I can, and properties really help with that. If you’re unsure on how these properties work, you can find more information In this part of the Microsoft documentation.

The Character Scriptable is probably a little easier to digest:

namespace ACHNarrativeDriver.ScriptableObjects

{

[CreateAssetMenu(fileName = "NewNarrativeSequence", menuName = "ACH Narrative Driver / Character")]

public class Character : ScriptableObject

{

[SerializeField] private string _name;

[SerializeField] private List<Sprite> _poses;

[SerializeField] private Sprite _nameplateSprite;

public string Name => _name;

public IReadOnlyList<Sprite> Poses => _poses.AsReadOnly();

public Sprite NameplateSprite => _nameplateSprite;

}

This is mostly straightforward. The name is the name of the character and the list of sprites are the different poses the character can have. The nameplate sprite is something specific to the game jam - since I was writing the narrtive tooling, I was also responsible for handling UI rendering - and the character’s nameplates were all different! So I just stored it in here for my canvas to use later.

And the last scriptable that matters to this tool, is PredefinedVariables:

namespace ACHNarrativeDriver.ScriptableObjects

{

[CreateAssetMenu(fileName = "NewNarrativeSequence", menuName = "ACH Narrative Driver / PredefinedVariables")]

public class PredefinedVariables : ScriptableObject

{

[Serializable]

public class VariableNameValuePair

{

[SerializeField] private string _key;

[SerializeField] private string _value;

public string Key => _key;

public string Value => _value;

}

[SerializeField] private List<VariableNameValuePair> _variables;

public IReadOnlyList<VariableNameValuePair> Variables => _variables.AsReadOnly();

}

}

This one does what it says on the tin, mostly - it is a list of predefined variables for the NarrativeSequence to consume. The name is a bit misleading however - I think a better name would’ve been PredefinedConstants since these values were mostly just baked into the scripts at compile time by the end of the jam. We’ll explore this in a bit when we look at the compiler(?) internals.

When brought together, these types make up the bulk of the game. I am completely serious. There is more data in these scriptables than there is actual code. So, lets quickly talk about the why.

OK…but why?

There are a few key questions I like to adhere to when writing any system for a game.

- Who is going to be using the system?

- How complicated is the system?

- How versatile does it need to be?

The first question here is fairly straightforward; this tool is being used by narrative writers. I literally know nothing about what might get written, so I have to support a featureset with this in mind in the broadest strokes possible.

The second question is a tad more involved. Parsing is never that simple of a task, and given what the symbols and narrative dialogue actually semantically mean, organising the narrative tool around data simply makes more sense. A lot of newer developers might be eager to hard-code data like this into codebases, but when you don’t know how many files of data you have to process, that is not maintainable and will get out of hand fast. Data oriented design, both as a programming principle and as a general rule of thumb, means your code becomes more like infrastructure. This is only a good thing, given how complicated games get. You want things to be broad and flexible. Scriptables help a ton with this approach, as they just function as inert data that the infrastructure can react to.

The last question sort of speaks for itself, and only reinforces my point around having well-defined data, and lots of it, being a good thing - narrative writers are not programmers. They want to write things like they are writing a book or a stage play. It is up to the infrastructure to represent that in a way that Unity can understand.

Overall, driving 90% of things with data will just make your life far easier. If you can design around data composition, as I have done here, getting flexible and maintainble behaviour in a video game is completely possible.

OK, are we all up to speed now on these implementation details? Great! Because they’re not changing now and the rest of the series wouldn’t make sense if they did, so, oh well! Onto the next part!

Game Jam Bundle!

If what I have been working on in this series has interested you, or you just want to play the finished game, you can get the game as part of a small bundle or $3 as part of an autistic charity fundraiser. I’d really appreciate it if you spent the money for a good cause, as this is something that’s very personal to me. Plus, the game is not finished, we have more content to add, so definitely more to look forward to from a gameplay perspecrtive! You can find the bundle here, and we would really appreciate your financial suport if you can spare it!